Timeless Writers are Hypnotic Writers

by Nerea San Jose D. Hyp, M.Phil, MA, BSc (Hons), MBSCH

Abstract:

This article suggests the reasons behind some writer’s timeless quality, why their work is endlessly read and re-read, while others fall into oblivion. We come to the conclusion that these writers are hypnotic writers. Hypnotic writing is full of metaphors and this article states the importance of Joyce and Crowley’s research on the three levels of communications in metaphors. Their proposal throws some light on the reasons behind these timeless writers in literature.

In literature, one of the biggest challenges is to understand the reasons behind some writers’ timeless quality, why their work is endlessly read and re-read, while others’ fall into oblivion. This article tries to explain the secret behind becoming a ‘timeless’ writer, which is to be a hypnotic writer.

When a writer uses three important elements in his story, he can become a timeless writer. It is proposed that these three elements are a) good character-plot, with metaphoric language, b) the interlocking of stories with metaphors, and c) ‘blind spots’. These elements are the most important ingredients for a story (be it a book, play, poem, or other format) to be read across cultures and eras. Cervantes, Shakespeare, and Agatha Christie, amongst others, used these elements and became hypnotic writers. They told stories in a way that meant readers could identify with the characters easily, and that the readers themselves would gain something from the situation and journey portrayed. This article is going to analyse metaphor and its function in a story, and also to prove that timeless writers are unconsciously using therapeutic metaphors.

Since the beginning of time, human beings have used storytelling to explain the reality around them. Myths, fairy tales, and community storytelling were there, in and affecting our minds, even before written words. From an anthropological point of view, myths are the community experience, and the first way in which we organised the collective memory. Myths don’t explain our reality per se, but they organise the world in a meaningful way. One example is Amari, the Basque myth (Ortiz-Oses & Garagalza; 125) as an archetype of Mother Earth. Amari is the foundation of the Basque society, and the identification of the Witch controlling the four elements of Mother Earth. In this way, the myth serves as a common shared memory in the Basque society, one which you can find similar versions of in other cultures across the globe. This collective memory shapes our verbal and nonverbal associations, where metaphors play an important role.

We can ask ourselves if the primitive men used metaphoric thinking regardless linguistic communication was not fully developed. The research done by Gillan, Premack, and Woodruff (1981) showed that their chimpanzee, Sarah, could identify missing pieces from a sequence. Understanding this is the first step in understanding a metaphorical cognitive structure; Sarah demonstrated possession of a cognitive process of relationships between ideas, required to grasp the meaning in any metaphor. This ability is clearly key to our evolution; the human brain uses and, we even dare to say, needs this kind of metaphorical language.

For Aristotle, a metaphor meant the act of giving a thing a name that belongs to something else. Diomedes described metaphor as the transferring of things and words from their proper signification to an improper similitude. This is something that is done in language and literature for the sake of beauty, necessity, polish, or emphasis (Burns G. W. 2007; 4). We use metaphors to acquire cognition and problem-solving strategies. We can see this parallelism of plot and acquisition of cognition in Don Quixote, by understanding the function of these elements in a timeless story.

On one hand, we can find very clearly the metaphors immerged in other metaphors, by the interlocking of the short stories, as part of the main plot. This is one of the similarities between literature and therapeutic metaphor’s framework.

On the other hand, the story presents ‘blind spots’, as Salvador Olivia claims ‘Macbeth’ does. Timeless writers have a pattern of presenting a blind spot where a detail is left unresolved, allowing the reader to choose his/her ending, consequences, or actions. This blind spot, during the story, is used in therapeutic metaphors. It is the moment where the reader/listener contributes to the unconscious process, and finds the unconscious similarities between their life and the story told.

Timeless writers, like Cervantes with Don Quixote, or Shakespeare with his plays, use metaphors that facilitate the identification of a personal reality (the reader’s one) with the story being narrated. Their language – their use of words – is the gateway to this identification in which the characters, and the right mind-set of the person, emerge as a new reality with personal meaning.

Metaphor in literature is a form of symbolic language which is used to explain or describe something. We use metaphors because we can convey an idea in an indirect yet paradoxically more meaningful way (Joyce 2014; 3). It is also a linguistic device and a cognitive construct that implies comparison between two unlike entities (Stott 2010; 5). All cultures, tribes, or families use metaphors in their language. We find them in the koans, Western fairy tales, or in indigenous philosophies, always used to explain the natural world. Metaphor, as an explanation of our world, is an enigma which provokes a deeper quest for knowledge (Joyce 2014; 7). It is a means of communication that is expressive, creative, perhaps challenging, and powerful. From the point of view of therapy, it is a language-based process of healing, heavily reliant on the effectiveness of communication between client and therapist, and a metaphor is the best way to facilitate the client’s process of change (Burns 2007; 4).

I would like to clarify that not all stories are therapeutic metaphors, but they work in a parallel manner. From my point of view, the jump from being a simple story into a therapeutic metaphor is more related to the listener (reader), and its identification processes with the characters, than the original intention of the writer. This is why some people have a different level of emotional reaction to a story, regardless of the fact they were presented with the same words.

All stories have common elements. Both types of metaphors (literature and therapeutic) describe something, and there is a correspondence with an experience. With the linguistic description we can alter, re-interpret, and reframe an experience. But in order to be a therapeutic metaphor, the writer needs to evoke a relational familiarity based on a sense of the listener/reader’s own experience, and familiarity with the linguistic language. That is to say, let them understand the words and use them as the language of their inner voice.

Timeless writers use stories so that the plot acts as a therapeutic metaphor because they (metaphors) answer the curious unconscious mind by giving solutions to a problem, or by showing resources and abilities that the listener/reader already has within them.

The famous fight of Don Quixote against the mill, for instance, evokes the strength, self–belief, and determination of tackling a problem. We all feel sympathy for Don Quixote, who tried to deal with the giant (the mill) in a fearless manner. No doubt many of us would like this determination and strong attitude to deal with some problems at some point of our lives, or even to have that blind certainty in a business plan, regardless of whether the bank (as a giant) may not agree with us.

Carl Jung considered fairy tales to be projections of the collective unconsciousness. All human consciousness is one; regardless of coming from different cultures and religious backgrounds, we all share a common consciousness and therefore all use similar symbols that represent both the lowest and highest aspects of human psychic life. The main function of the symbol is to portray ‘archetypes’, or primordial images (Rowshan 1997; 23- 25).

A well-described character in a story will symbolise elements in each individual, and Carl Jung understood the importance of metaphors and their symbolic presentation of psychological archetypes. This symbolism helps to increase the identification of the story’s audience with the story, opening the doors to different outcomes or ways of dealing with the situation described. According to Jung, the lowest and the highest aspects of our “Self” are manifested through the use of symbols. Symbolism and metaphoric writing are very similar from this perspective, because a word – or an image – is symbolic when it implies something more than its obvious and immediate meaning, and it has a wider ‘unconscious’ aspect that is never precisely defined, or fully explained, as Joyce states (2014; 10). We must also consider the great importance of condensed symbols. Condensed symbols have more than one meaning; they are multivocal and have a strong emotional quality (Wirtztum 1988).

Metaphors also show sub-personalities, which are defined as different aspects of the self which come to the fore in different situations, and with which we may then become identified (Water 2010 & Rowan 1993). A well-written metaphor will touch the listener/reader in a particular and relevant way (Joyce 2014; 49). It creates a shared experience – the ‘you are not alone’ factor.

How many times have we read or watched an Agatha Christie mystery, and from the very beginning of the book tried to guess who the killer is? And how many of us have we carried on reading to find out if we were right? The majority of us! And even if we knew who the killer was, we carried on reading the words because the description of the characters related so much to our own personal experiences (or collective consciousness) that we didn’t mind if we knew the end of the story.

Metaphors offer two levels of communication: conscious and unconscious. These allow the creation of inner unity and the grounds for an emergent relatedness. Kopp stated that there are three basic modes of knowing: 1) rational; 2) empirical; 3) metaphorical, which help us shape the world that we live in, make sense of it, and manipulate it (Kopp 1972; 8).

Julian Jaynes extended Kopp’s point of view and stated as his hypothesis that the subjective conscious mind is the process of any metaphor (Jaynes 1976). In Jaynes’ opinion, metaphor is a primary experience that serves a twofold purpose: a) describing experience and b) generating new patterns of consciousness that expand the boundaries of subjective experience (Joyce 2014; 19).

When we read Don Quixote, we find many metaphors that generate new patters of consciousness in the reader. We might describe these stories as unrealistic, stupid, or simply funny, but they are the foundation on which the therapeutic metaphor can do its work. The therapeutic metaphor allows us to be in a different setting or see ourselves filling the shoes of another person.

As an example of this, Cervantes presents Sancho demanding from Don Quixote the fulfilment of his promise of making Sancho a governor. Everybody identifies this with the desire of being a director, manager, or someone with power and independence to do whatever he/she wants. The story shows the difficulties that Sancho and Don Quixote have to endure until they realise that they need each other. And their togetherness makes the perfect team to cope with whatever difficulties life brings them. From a child’s point of view, this story ends with two friends becoming friends again after a conflict. On the other hand, from an adult’s point of view, we might see a political message from the author: an implied criticism of the establishment of the century. In either case, the metaphor does its work by finding a way into our subjective experience and allowing the creation of new patterns of consciousness, behaviour, or thought.

Timeless writers play with their words in a particular way so that not only do we identify with the experiences narrated, but also find them communicating directly into our brain, as it were. Our brain is shaped to use metaphors not only on a linguistic level, but also on a psychosomatic level. Rossi and Erickson understood the great importance of metaphors during therapy, and therefore the great importance of storytelling, drama, and myths for our understanding and interaction with our world. They stated the parallelism of the linguistic metaphor (characters’ portrait) and the physiological characteristics of right-brain functioning. Listening to or reading a metaphor will increase the brain activity in the right hemisphere which deals with imagistic, implicative, contextual, and fluid information. At the end of the day, all our information comes into the right hemisphere first, and then, the left hemisphere analyses and takes what needs to be taken. The end result of this process is that all the information from the left hemisphere comes back to the right hemisphere again, for us to be able to have a contextual view, a wholeness to our interpretation of the world (McGilchrist; 2012).

We can go further, and remember the words of Siegel, who claims that the mind, as a fundamental part of our humanity, is shaped by story (Joyce 2014; 19). The neuroplasticity of our brain shows how we react to experiences and metaphors, allowing the brain to change structure according to its needs. Therapeutic metaphors use this ability of the brain to find new ways of responding to a particular experience. The research done by Dr. Doidge ( Doidge, 2007; Chapter 8) proved that imagining an act engages the same motor and sensory programs involved in doing it for real. Hypnotic writers evoke in our minds the body-mind actions as a behaviour being done by us.

If we identify the elements of a therapeutic metaphor, we also recognise the linguistic metaphor and its importance when presenting minimal cues during the description. The minimal cue is the description done, in detail, by noticing all the six senses: visual, kinaesthetic, gustative, olfactory, auditory, and proprioceptive.

Elements of a therapeutic story based on Joyce research (Joyce 2014; 14):

- A conflict or situation that needs a resolution.

- Personify unconscious process: archetypes hero/villain.

- Personify parallel possible learning of outcomes.

- Presenting the crisis and its resolution where the main character overcomes the situation. Awareness of minimal cues in the description.

- The new pattern of identification and purpose: identification with our own senses.

- Finally, the story ends with a celebration and acknowledgement of the new resolution.

This general view shows us the structure of a therapeutic story and its similarity to a non-therapeutic story. The main different is in the level of identification with the character and the situation. For a story or metaphor to be therapeutic, it has to evoke specific responses in the reader/ listener. Evoking a relational and familiar situation, or crisis, allows the unconscious and conscious processes to elaborate new responses, so that the reader/listener makes it their own. You say to yourself: I would have done the same thing, or acted differently if…!

Cervantes, Shakespeare, and Agatha Christie do this with their writing. The simplicity of presenting the situation and the in detail description, using verbal and non-verbal minimal cues, makes their writing work as the perfect metaphors to engage the reader and allow the conscious and unconscious to emerge with a new mental process.

If we go back to the moment where Sancho demands Don Quixote fulfil his promise; the knight is not sticking to his promise so the frustration that Sancho feels while talking to his master is something we can understand, and also identify with the desire for our own increase of salary or position at work. Later on in the story, the situation of Sancho being given the post as a governor, and the difficulties he has to endure, can be replicated in the modern reader, again in the desire of a better position at work, but we are also aware of the loneliness Sancho might feel without his colleague. From Cervantes’ point of view, it shows that society doesn’t allow this sudden change of social status, and that we all have a place, a time, and a role to play in life. Cervantes allows the readers, from the XVII century, to dream of the possibility of changing their social status. The resolution of the crisis shows that we all can dream, even make our dreams come true in relation to wealth, food, and power, but this may have a non-desired outcome, or a consequence that we didn’t foresee as a result of the new situation.

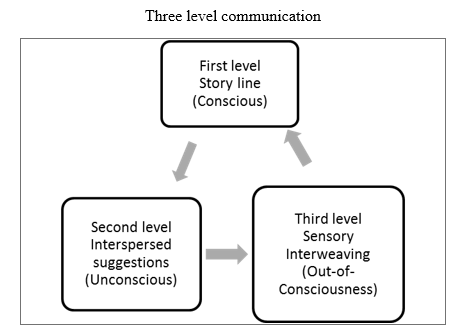

Joyce (2014; 78) points out that these minimal cues, which facilitate the identification process during the description in a story, allow us to understand the importance of the process of metaphors as a three level communication. She proposes the following figure (Joyce 2014; 103):

In my opinion, the three levels of communication are also related to the writing style that makes people from all cultures read a story. The first level is the plot; evidently you need a good plot with strong characters. This plot will give unconscious, personalised meaning to the words for each individual.

The second level is the interspersed suggestion. This is the level of unconscious meaning, where the sensory language is the key to identification. This level is the second meaning that we process – under the words – while they are telling the plot of the story. Here the minimal cues are of upmost importance, together with the dynamics of the language (or voice used). We understand better this level if we acknowledge human activity as a whole with verbal and non-verbal structure (Roulet 1976; 17).

Finally, the third level is the sensory interweaving of the out-of-consciousness. There are several systems when we speak or process a story. Heller and Steele ( Heller & Steel 2011) added the out-of-conscious/unconscious system to the other systems: conscious output, unconscious input (eye movements), and body language (including the proprioception system).When an individual finds it difficult to make conscious any information from any system – kinesthetic, auditory, or visual – they are using, according to Heller and Steele, their out-of-conscious system. This is the moment where our minds are opened and actively seek to do something about a specific problem or thought. Heller and Steele understood the importance of the sensory system of out-of-consciousness, and its relation to sensory-rich language. Here is where the ‘blind spot’ triggers the third level of sensory interweaving in the reader. The out-of-consciousness cue is presented as something that can be resolved.

If we analyse the written word ‘said’ in literature, we understand that we don’t get the same effect if we use words like ‘claimed’ or ‘stated’. Using colloquial language in a written plot allows us to feel that we are actually listening to the information rather than reading it; therefore we make ourselves part of the conversation and we better internalise the words used into our unconscious mind.

Timeless writers present to their readers a metaphoric language which exposes their mind to several components of cognition (Stott 2010; 19):

a) Awareness of imagery as a simulation of embodied experience necessary to understand the metaphor. With this understanding we can ‘grasp’ another domain of knowledge that might help us in one way or another. Lakoff and Johnson explain that the target domain is shaped by our concept of the source domain. We can see this example (Stott 2010; 10):

Life is a journey

Life as target domain

Journey as source domain

b) Integration of verbal and imagined cognition to our own experience in a flexible way (Kopp 1995).

c) Holding to concepts in mind. This is the ability to hold more than one thought in awareness at one time, and this ability promotes problem-solving processes in the reader/listener. Metaphoric writing uses more ‘covert’ techniques, which rely on imagery. Imagery in a hypnotic metaphor enhances the application of new behaviours by the identification of the reader/listener with the character in the story (Fezler; 169).

d) Awareness of commonalities despite superficial differences. Lakoff and Johnson (Lakoff & Johnson 1980) claimed that metaphors help to find similarities between two aspects of cognitions despite the superficial differences between them. This ability is considered to be a highly adaptive cognitive skill.

e) Flexible use of multiple meanings. It is useful to alternate between metaphors that capture different facets of a concept, as Richard Bandler does in his talks – leaving unfinished metaphors hidden in his unfinished stories like a Russian doll. Don Quixote is a great example of a metaphor inside another metaphor, allowing the mind of the reader to become flexible and open to all sorts of situations with unconscious meanings.

We can agree with Burns’ statement (Burns 2005) about the employment of words in metaphors, healing stories, or therapeutic tales. A metaphor is used with the purpose of emphasizing that this is neither just a casual, anecdotal account nor an inconsequential tale such as we may relate at a party. By metaphor, or healing story, Burns refers to a deliberately crafted story that has a clear, rational, and ethical therapeutic goal. It is, in other words, a tale that is based on our long human history of storytelling, grounded in the science of effective communication, demonstrating specific therapeutic relevance to the needs of the client, and told with the art of a good storyteller.

From this point of view, we can claim that Cervantes, Shakespeare, and other authors are therapeutic writers. Their objective wasn’t only to entertain the reader or listener, they also had a message to convey. They wanted their audience to feel something new, deep in their souls. As Erickson & Rossi (Erickson & Rossi 1976; 225) state, metaphors and folk language can be understood as presenting a general context on the surface level that is first assimilated by consciousness. Therefore, we can say that the language used – the particular words expressing the minimal cues – to articulate that specific context also has its own individual and literal associations that do not belong to the context given in the story or metaphoric plot. Timeless writers facilitate these suppressed associations ‘locked’ in the out-of-consciousness to become a new responsive behaviour to the conscious mind.

In our opinion, with these arguments we have uncovered the secret behind timeless writers. They are hypnotic writers; that is to say, writers who use metaphors correctly will be taken their first steps to becoming a well-read author throughout cultures and time, as Cervantes has. Don Quixote is the most translated story in the word; the cross-cultural understanding of being a dreamer and a fool – someone with a good heart and honour but putting himself in unusual or problematic situations – makes everybody dream, when we read Cervantes’ words, of this Knight looking for justice.

Bibliography:

Burns, George W. (2005): 101 Healing stories for Kids and Teens: using Metaphors in Therapy. New Jersey, John Wiley &Sons.

Burns, George W. (2007): Healing with stories: your casebook collection for using Therapeutic Metaphors. New Jersey, John Wiley &Sons.

Cervantes, Miguel de (1965): El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don quijote de la Mancha. Madrid, Colección Austral, Espasa-Calpe.

Doidge, Norman (2007): The brain that changes itself. Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science. Kindle edition.

Erickson, Milton H.; Rossi Ernest L.; Rossi, Sheila L. (1976): Hypnotic Realities: The induction of clinical hypnosis and forms of indirect suggestions. New York, Halsted Press.

Fezler, William D. (1977): “Learning theory, hypnosis, behaviour modification, and imagery conditioning”. Chapter 31 in Kroger, W. S. (1977): Clinical and experimental hypnosis in Medicine, dentistry, and psychology. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Gillan, D. J.; Premack, D.; Woodruff, G. (1981): “Reasoning in the Chimpanzee .1. Analogical Reasoning”. Journal of Experimental Psychology-Animal Behaviour Processes, 7,(1),p. 1-17.

Hammond, Corydon D. (1990): Handbook of Hypnotic Suggestions and Metaphors. An American society of clinical hypnosis book.

Heller, Steve; Steele, Terry L. (2001): Monsters & Magical Sticks. There’s No Such Thing as Hypnosis? Arizona, New Falcon Publications.

Joyce, C.M.; Crowley R. J. (2014): Therapeutic Metaphors for children and the child within. New York, Routledge.

Kopp, Sheldon (1972): If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him. Palo Alto, California, Sheldon Press.

McGilchrist, Iain (2012): The Master and his emissary: the divided brain and the making of the Western World. London, Yale University Press.

Olivia, Salvador: ‘The Problem of Evil in Studies of ‘Macbeth‘. Cervantes and Shakespeare: 400 years. An Anglo-Spanish Symposium at University of Oxford.

Ortiz-Oses, Andrés; Garagalza, Luis: Mitología Vasca: todo lo que tiene nombre. Kutxa fundación/Nerea. Sin año.

Roulet, Eddy (1976): Lingüística y comportamiento: el análisis tagmémico de Pike. Traductor José Zahonero. Valencia, Marfil.

Rowshan, Arthur (1997): Telling Tales: how to use stories to help children deal with the challenges of life. Oxford, One World Publications.

San José, Nerea (1989): Una nueva perspectiva Epistemológica para el hombre: la comunicación no verbal. Tesina dirigida por Dr. Nicanor Ursua Lezaun, Universidad del País Vasco.

Scott, Richard; Mansell, W.; Salkovskis, P.; Lavender, A; Cartwright-hatton, S. (2010): Oxford guide to Metaphors in CBT: building cognitive bridges. Oxford, University Press.

Siegel, Daniel J. (2012): The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are, Second Edition. Guilford Press.

Waters, Trisha (2010): The use of therapeutic story writing to support pupils with behavioural, emotional and social difficulties. Thesis for PhD, University of Southampton.

Wirtztum Eliezer; van der Hart, Onno; Friedman, Barbara (1988): “The Use of Metaphors in Psychotherapy”. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 12/1988; 18(4):270-290. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/253853518_The_use_of_metaphor_in_psychotherapy

Nerea San Jose D. Hyp, M.Phil, MA, BSc (Hons), MBSCH is a therapist in London, UK.

web site: www.ahypnoticsolution.com